Magnetic coil springs accelerate particles on the Sun

Why does the Sun sometimes accelerate preferentially helium-3 and iron into space? Researchers have for the first time observed helical solar flares as a source.

In April and July 2014, the Sun emitted three jets of energetic particles into space, that were quite exceptional: the particle flows contained such high amounts of iron and helium-3, a rare variety of helium, as have been observed only few times before. Since these extraordinary events occurred on the backside of our star, they were not discovered immediately. A group of researchers headed by the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) and the Institute for Astrophysics of the University of Göttingen (Germany) present a comprehensive analysis now in the Astrophysical Journal. It is based on data from the twin space probes STEREO A and STEREO B, which – at that time still both operating – were in a favorable observation position behind the Sun at the crucial time. For the first time, the study shows a correlation between helium-3 and iron-rich particle flows and helical eruptions of ultraviolet radiation in the Sun's atmosphere. These could provide the necessary energy to accelerate the particles into space.

Sudden particle emissions, in which our star repeatedly hurls large amounts of charged and uncharged particles into space, are still a mystery. Some of these particle flows are accompanied by violent solar flares, a sudden and local increase of the Sun’s brightness, and contain up to 10,000 times more helium-3 and up to 10 times more iron than the Sun's atmosphere. Why is this extremely rare helium isotope accelerated into space so efficiently? And why iron? How does the Sun supply these particles with the necessary energy to catapult them into space?

"The events, that took place on the backside of the Sun in April and July 2014, were particularly intense and allowed for unusually extensive insights”, says Dr. Radoslav Bučík from the MPS. Only seldomly does the Sun emit particle flows so heavily enriched in helium-3 and heavier elements into space – and often they do not originate from the “right” place. Most space probes studying the Sun do so from an observational position close to Earth. They therefore see only the side of the Sun facing the Earth. Only the spacecraft STEREO A and B, which have been orbiting our star from opposite sides since 2006, began to observe the Sun’s far side in 2011.

Shortly before the control center lost contact to STEREO B in October 2014, both probes witnessed the "hidden" particle eruptions on 30 April 2014 and 17 and 20 July 2014. The eruptions lasted up to three days each. "The amount of helium-3 and iron in them was increased as much as in just a handful of other known events," Bučík describes the measurements.

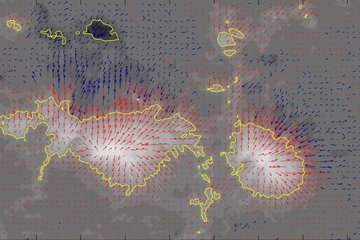

While the ion telescope SIT (Suprathermal Ion Telescope) on board the STEREO probes recorded the composition of the particle streams, the EUVI instruments (Extreme Ultraviolet Imager), parts of STEREO’s instrument package SECCHI (Sun Earth Connection Coronal and Heliospheric Investigation), looked at their regions of origin in the atmosphere of the Sun. There, the scientists found the typical increase of extreme ultraviolet radiation, which is usually accompanied by particle events of this kind, but this time in an unfamiliar form: helical movements were clearly recognizable.

"This is the first time that we have seen a twisted radiation outburst as the source of helium-3 and iron-rich particle flows," says Bučík. The radiation is caused by hot plasma moving along the constantly swirling and changing magnetic field lines in the Sun's atmosphere. When these field lines regroup, there may be a sudden release of energy. "The helical magnetic fields seem to efficiently provide helium-3 and iron in the solar atmosphere with energy - much like a spring coil that is suddenly released," said Bučík.

"Only by further exploring this mechanism can we better understand other solar outbursts," says Dr. Nariaki Nitta of the Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center in Palo Alto, USA. The researchers’ focus is particularly on a further variety of particle events, so-called coronal mass ejections (CMEs). The energy of these particles is very high. They can lead to solar storms on Earth, which endanger, for example, satellites. In rare cases, these ejections are also very rich in iron - and then particularly dangerous because of the particles’ high mass. The researchers now want to investigate whether these iron-rich particles outbursts, too, are accelerated by helical radiation bursts.

This research project was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and the Max Planck Society (MPG).