Dawn: Final signal from the asteroid belt

After more than eleven years in space, NASA’s spacecraft Dawn has ceased to communicate. The space probe’s hydrazine fuel is depeleted; the operational mission has come to an end.

Dawn, NASA’s mission to the asteroid belt, has come to an end. The spacecraft, that was launched in 2007 and has been exploring the asteroid belt since 2001, has run out of its hydrazine fuel, which enables it to control its pointing. This is necessary to transmit and receive signals to and from Earth. After Dawn missed scheduled communication sessions on 31 October and 1 November, NASA concluded that the mission is over. During the course of the mission, Dawn's Framing Cameras, developed, built and operated under the leadership of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany, has captured more than 100000 images of Vesta and Ceres, the two largest objects in the asteroid belt.

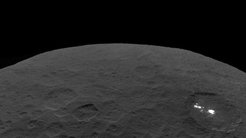

This photo of Ceres and the bright regions of Occator Crater was one of the last views NASA's Dawn spacecraft transmitted before it completed its mission. This view, which faces south, was captured on Sept. 1 at an altitude of 2,340 miles (3,370 kilometers) as the spacecraft was ascending in its elliptical orbit.

The end of the Dawn mission comes as no surprise. Since June of this year, Dawn has been flying strongly elliptical orbits around dwarf planet Ceres bringing the spacecraft within 35 kilometers of the surface. Under these conditions, mission managers expected the fuel supply to be exhausted most likely between mid-September and mid-October. “We are thankful for every day that Dawn has surpassed these expectations and for every data packet we have received since then”, says Dr. Andreas Nathues from MPS, Framing Camera Lead Investigator.

Since March 2015, Dawn has been exploring the mission’s second target, the dwarf planet Ceres located within the asteroid belt. Ceres has proven to be complex body with water reservoirs stretching beneath its surface and evidence of cryovolcanism. Dawn’s first target, the giant asteroid Vesta, in contrast is a rocky world, that was once well on its way to becoming a planet.

"The Dawn mission has not only fundamentally changed our view of the asteroid belt," says Nathues. "It has also been invaluable in understanding how the solar system as a whole emerged and where conditions favorable for life could evolve," he adds. Dawn’s scientific camera system, the Framinf Cameras, have played a crucial role in this endeavor. The tens of thousands of images of Vesta and Ceres obtained in this way will be evaluated for years to come.

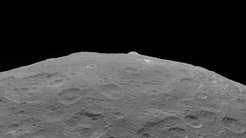

This photo of Ceres and one of its key landmarks, Ahuna Mons, was one of the last views Dawn transmitted before it completed its mission. This view, which faces south, was captured on Sept. 1 at an altitude of 2220 miles (3570 kilometers) as the spacecraft was ascending in its elliptical orbit.

The spacecraft itself will remain in the asteroid belt - "parked" on a stable orbit around Ceres. The water-rich dwarf planet will continue to be of great interest to scientists who are concerned with the necessary conditions for the emergence of life. A dive or a landing on Ceres - as happened with the Cassini and Rosetta missions - was therefore out of the question. This could contaminate the dwarf planet with terrestrial microbes. According to NASA, Dawn will be able to maintain its current orbit for at least 20 years. With a probability of more than 99 percent, the spacecraft may even remain on this trajectory for more than 50 years.

Dawn's mission to Vesta and Ceres is managed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory for NASA's Science Mission Directorate in Washington. Dawn is a project of the directorate's Discovery Program, managed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. UCLA is responsible for overall Dawn mission science. Orbital ATK, Inc., of Dulles, Virginia, designed and built the spacecraft. JPL is managed for NASA by the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. The framing cameras were provided by the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Gottingen, Germany, with significant contributions by the German Aerospace Center (DLR) Institute of Planetary Research, Berlin, and in coordination with the Institute of Computer and Communication Network Engineering, Braunschweig. The framing camera project is funded by the Max Planck Society, DLR, and NASA.